Back to history. Before New York became the nation's industrial center with a vast immigrant labor force living in it, politicians were elite patricians, stewards of the entire city, not representing one or another constituency. They were somewhere between a pastor and a business owner. Of course they did represent their elite business interests, but the paternalist view held that the elite knew what was best for everyone, not just for some.

With the growing mass of voting immigrant labor, the possibility of winning office by appealing to a particular constituency emerged. A Democrat politician, Fernando Wood (he was named after a fictional romance hero, no ethnic implication), seized the opportunity, becoming New York's first populist mayor, winning election by catering to the working class.

This was a new kind of politics, a new kind of rule of administration and a new game of playing one group against another. It incited fierce political divisions since the interests were no longer ordered from the top, but pitted against one another, wealth against poverty, top against bottom, native against immigrant, laborer against owner, and in the fray every interest in between had now a card to play. Fernando Wood was the first modern New York politician.

He's usually depicted as a racist opportunist. He was, of course, but this is a naive view. He was first and foremost a champion of labor. He created the first public works project to give immigrants jobs at a time when those immigrants were mostly Catholics and deeply despised, disparaged and resented. No doubt for him it all fed his opportunism, but that's modern politics, isn't it? Constituency opportunity -- that's what he brought to the table. No more Platonic paternalism of the wise elite ruler, politics is now sheer power of numbers of the voting block. It was a political revolution, for better or worse.

It led to violence and a bitter antagonism between the city and the state, which was not interested in the city's Catholic working class. Following the police riots -- the city police force fought with the newly created state police on the steps of City Hall -- New York was left spectator to police rivalry until it became lethal in the Dead Rabbit riots in the heart of the ghetto. The entrenched antagonism between immigrant and native, Catholic and Protestant, labor and elite, Democrat and Republican, recast the meanings of New Yorkers and the profile of the city's character and fate. When Wood first took office he found it an ordered, integral city of class distinctions of rich owners and poor laborers; he left it a battle ground of class struggle and complex political divisions based on that struggle.

He was also an anti-abolitionist. During the Civil War he recommended the city secede from the Union in order to remain neutral in the war and to continue trade with the South. How could he be so progressive on labor and still support slavery? The South was New York's biggest trade partner. Labor -- white labor -- relied on it.

Today Americans wonder what happened to the Republican Party that had been the party of Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt and is now the party of Bushes, , Cheney, Kochs, Cruz and even Trump. But there really was no change -- it's our perception that has changed. The Republican Party has always been the elite party even when Lincoln was its candidate. Abolitionism among whites was an elitist movement. Labor was against it. Labor viewed it as divisive and therefore unpatriotic, destroying the unity of the nation. It was also perceived as bad for labor in the North which depended on the clothing trade and cotton. Labor saw abolitionism as a moral extravagance of the wealthy who lectured overseas on the moral turpitude of American society (see Burroughs&Wallace's Gotham). In short, labor viewed abolitionists as traitors who cared more about slaves than wage-laborers.

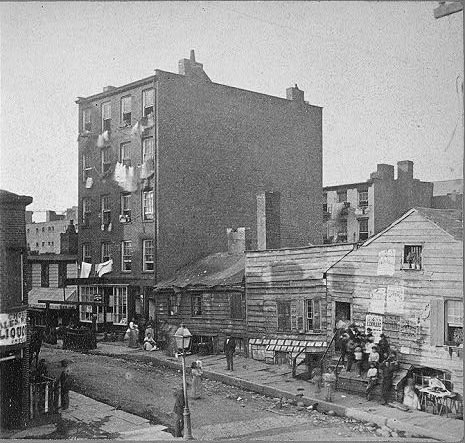

These differences erupted in the Draft Riots, a race riot cum attempted labor revolution. Following the riots, the Democratic Party seems to have recognized that Christmas turkeys did not suffice to buy labor's vote. Tammany Hall had to produce. The result was a series of housing laws to improve the quality of living in the ghetto. It was the beginning of the transformation of the tenement culminating in the New Deal, those nation-wide reforms first initiated in NY -- all from its origin in the Draft Riots, probably the most important event in the city's history and certainly its turning point and perhaps a turning point for the progressive movement towards the modern welfare state; without the Draft Riots, no New Deal.

%20(1).jpg)