Wednesday, August 06, 2014

Franchisee labor win

The NLRB (National Labor Relations Board, the agency that rules on labor issues) has decided that employees of a franchisee can name the corporate franchisor in complaints, strengthening labor's voice and requiring greater responsibility from corporate giants. It should be good for the franchisees as well to have the franchisor taking responsibility for labor relations. It's astonishing that MacDonalds previously had not been accountable for labor violations in their franchise stores.

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

Piketty and immigration

Just finished Piketty's Capital in the 21st Century. His central claim is that the ratio of capital/labor increases as the rate of economic growth decreases because the rate of return for capital remains constant, and, he claims further, the growth rate will decline through the rest of the century as the population rate (the rate, not the absolute population) declines.

He recommends a tax on wealth/capital. But if he's right that the rate of growth will decline ceteris paribus, seems to me his wealth tax is not the only option: opening the borders should slow wealth inequality. Open borders w/naturalization would also counterbalance the political influence of wealth, Piketty's underlying complaint against wealth accumulation.

His tax could happen in Europe, but not likely here in the US. How would a push for immigration fare as a means to grow the economy? With an alliance of business with immigrants? After all, Piketty's prediction is a ratio, not an absolute quantity of wealth or its buying power. r>g holds when g increases, even though the ratio of wealth-income decreases. It would be a win-win for business and immigrants. It should not hurt unions in the long run either, although in the short run it might hurt a lot.

Labels:

anti-coporate campaign,

chinatown,

deregulation,

economics,

labor,

macroeconomics

Friday, June 20, 2014

Rent regulation, Krugman, Yglesias and reality

A couple of years ago, when the city rent regulations were up for renewal, I wrote an analysis for Met Council to rebut Paul Krugman's standard but flawed complaint against rent regulations. In it I supressed a key force in the development market largely because it seemed at the time too pessimistic. But this morning it occured to me that there's much more to be said about it, and it's worth saying, especially now when there's no rent battle.

First to recap: Krugman's column was focused on San Francisco without recognizing -- or perhaps not knowing -- legal and market distinctions between that city and ours crucial to a clear understanding of the market and regulations here.

On his classic liberal economic view of rent regulations, it is assumed that regulations dampen development, suppressing supply so raising rents. It is also assumed that deregulation will push out current residents, increasing the supply of rentals, so lowering market rents. Rent regulations, on this familiar view that Krugman followed, are the cause of the city's housing crunch and the consequent excessively high market rates.

In the Met Council piece, I showed that both of these assumptions are false in New York City. Because they do not apply to new construction, NYC rent regulations do not dampen development. On the contrary, they are one of the very few incentives to develop in this city, rather than just price up existing apartments, a much cheaper option than construction. Deregulation prices up existing rents, so it de-incentivizes construction. So the first assumption is plainly false.

The second assumption is a bit less plain. When tenants are evicted by a rent hike, the tenants typically don't leave the local rental pool. Employment, family or cultural preferences tie them to the locality (for us, the larger metropolitan area). Instead, many move to cheaper neighborhoods, where, especially in a city where the supply is limited, they increase the demand for housing in those neighborhoods, raising rents there and in turn displacing the prior tenants.

The overall effect is one of musical chairs, not surplus. When everyone has found a seat and settled in, the rents should be exactly as high as before. And as long as newcomers arrive, the rents will continue to rise. with no relief to existing tenants.

The economic difference will be an increase in the aggregate funds available for rent as the formerly regulated tenants devote more of their income to rent and those who can afford more rent move up into those deregulated apartments. The increase goes to landlords.

If deregulated tenants have less disposable income as a result, they may contribute less to the consumer economy or contribute more to the workforce. Both are undesireable: the former dampens the economy, the latter, if it's significant, lowers wages in the workforce, which can also dampen the economy and increase inequality.

Both Krugman and Yglesias agree that construction would ease the market. That is certainly true, as far as it goes (and that is as far as I went in the Met Council piece). But this is liberal market utopianism: deregulate and the invisible hand of the market will provide through the balancing of the individual interests of both developers and residents. There is a diminishing return on construction. Once the supply exceeds the demand, construction will end and developers will seek greener pastures. Developers are mobile, so the construction market in NYC depends on the construction market elsewhere. The tight market everywhere serves the rentier.

Worse, NYC, unlike most places in the world, has a well of demand with no visible bottom. Build it and the wealthy will come. Upzoning, Yglesias' solution, brings newly constructed units to NYC but does not ease market rates, it merely upscales the city. Since apartments respond to cultural fetishes, the more new units constructred, the more old neighborhoods become attractive. A city, like any cultural artifact, defines itself by a value structure of differences as well as of uses suited to distinct motivations. The Lower East Side, once a ghetto (explicitly named as such in maps in the 1920's) for industrial labor and a place to avoid as a utilitarian necessity, now attracts urban youth who would find a penthouse in a glass building culturally sterile.

If, in NYC, new luxury rents were set at market rate and then regulated thenceforward, the incentive to construct might not be too much curtailed. But this will yield more luxury constuction, not more affordable housing, nor easing of the rental market.

When New Yorkers complain that the rents are too high, they forget that landlords charge the highest possible rate that tenants are willing (or, at the bottom, can) pay. Rents are "high" because renters (those above the bottom) want to pay (the bottom have to pay). They are at a negotiating disadvantage, since landlords hold multiple options including warehousing, while renters are mere individuals, unorganized.

If Krugman and Yglesias are wrong -- that is, are deregulation of rents or zonings ineffectual -- is there any way to lower rents? Regulating profit margin might work. It has an interesting precedent in city government. (Thanks to Bill Cashman who pointed this case out to me). Abu Dhabi, the owners of the Chrysler Building, pay its land owner, Cooper Union, the assessed real estate tax on the land. As a non profit, Cooper Union pays no tax. So the rent on the land is in effect determined by the city and state. The Rent Stabilization Board also regulates landlord profit, but it doesn't do this individually, and landlords' books are not open.

A simpler answer would be to place all land and buildings into public hands. If the city could extract a reasonable rent from the 1%, they'd easily be able to manage effectively the current NYCHA properties and even build more affordable housing. If renters were allowed to strike, landlords would eventually abandon their buildings and the city would inherit them. Too bad it'll never happen. It's the only sane solution to "the rent is too damn high!"

First to recap: Krugman's column was focused on San Francisco without recognizing -- or perhaps not knowing -- legal and market distinctions between that city and ours crucial to a clear understanding of the market and regulations here.

On his classic liberal economic view of rent regulations, it is assumed that regulations dampen development, suppressing supply so raising rents. It is also assumed that deregulation will push out current residents, increasing the supply of rentals, so lowering market rents. Rent regulations, on this familiar view that Krugman followed, are the cause of the city's housing crunch and the consequent excessively high market rates.

In the Met Council piece, I showed that both of these assumptions are false in New York City. Because they do not apply to new construction, NYC rent regulations do not dampen development. On the contrary, they are one of the very few incentives to develop in this city, rather than just price up existing apartments, a much cheaper option than construction. Deregulation prices up existing rents, so it de-incentivizes construction. So the first assumption is plainly false.

The second assumption is a bit less plain. When tenants are evicted by a rent hike, the tenants typically don't leave the local rental pool. Employment, family or cultural preferences tie them to the locality (for us, the larger metropolitan area). Instead, many move to cheaper neighborhoods, where, especially in a city where the supply is limited, they increase the demand for housing in those neighborhoods, raising rents there and in turn displacing the prior tenants.

The overall effect is one of musical chairs, not surplus. When everyone has found a seat and settled in, the rents should be exactly as high as before. And as long as newcomers arrive, the rents will continue to rise. with no relief to existing tenants.

The economic difference will be an increase in the aggregate funds available for rent as the formerly regulated tenants devote more of their income to rent and those who can afford more rent move up into those deregulated apartments. The increase goes to landlords.

If deregulated tenants have less disposable income as a result, they may contribute less to the consumer economy or contribute more to the workforce. Both are undesireable: the former dampens the economy, the latter, if it's significant, lowers wages in the workforce, which can also dampen the economy and increase inequality.

Both Krugman and Yglesias agree that construction would ease the market. That is certainly true, as far as it goes (and that is as far as I went in the Met Council piece). But this is liberal market utopianism: deregulate and the invisible hand of the market will provide through the balancing of the individual interests of both developers and residents. There is a diminishing return on construction. Once the supply exceeds the demand, construction will end and developers will seek greener pastures. Developers are mobile, so the construction market in NYC depends on the construction market elsewhere. The tight market everywhere serves the rentier.

Worse, NYC, unlike most places in the world, has a well of demand with no visible bottom. Build it and the wealthy will come. Upzoning, Yglesias' solution, brings newly constructed units to NYC but does not ease market rates, it merely upscales the city. Since apartments respond to cultural fetishes, the more new units constructred, the more old neighborhoods become attractive. A city, like any cultural artifact, defines itself by a value structure of differences as well as of uses suited to distinct motivations. The Lower East Side, once a ghetto (explicitly named as such in maps in the 1920's) for industrial labor and a place to avoid as a utilitarian necessity, now attracts urban youth who would find a penthouse in a glass building culturally sterile.

If, in NYC, new luxury rents were set at market rate and then regulated thenceforward, the incentive to construct might not be too much curtailed. But this will yield more luxury constuction, not more affordable housing, nor easing of the rental market.

When New Yorkers complain that the rents are too high, they forget that landlords charge the highest possible rate that tenants are willing (or, at the bottom, can) pay. Rents are "high" because renters (those above the bottom) want to pay (the bottom have to pay). They are at a negotiating disadvantage, since landlords hold multiple options including warehousing, while renters are mere individuals, unorganized.

If Krugman and Yglesias are wrong -- that is, are deregulation of rents or zonings ineffectual -- is there any way to lower rents? Regulating profit margin might work. It has an interesting precedent in city government. (Thanks to Bill Cashman who pointed this case out to me). Abu Dhabi, the owners of the Chrysler Building, pay its land owner, Cooper Union, the assessed real estate tax on the land. As a non profit, Cooper Union pays no tax. So the rent on the land is in effect determined by the city and state. The Rent Stabilization Board also regulates landlord profit, but it doesn't do this individually, and landlords' books are not open.

A simpler answer would be to place all land and buildings into public hands. If the city could extract a reasonable rent from the 1%, they'd easily be able to manage effectively the current NYCHA properties and even build more affordable housing. If renters were allowed to strike, landlords would eventually abandon their buildings and the city would inherit them. Too bad it'll never happen. It's the only sane solution to "the rent is too damn high!"

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

Concerning the history of real estate in the slum

Trying to attribute gentrification to the real estate industry, Neil Smith came up with an analysis that distinguished ground rent from building rent. It's an echo of David Ricardo, whose brilliant analysis of rent distinguished the value of the land from the value it produced in an agricultural economy. Smith's distinction is inventive and imaginative, but maybe not reflective of any economic reality. I think he conflated potential with real. To explain why I think so, I'm going back in time to the roots of slum real estate.

In her Manhattan for Rent (Cornell 1989), Elizabeth Blackmar recounts how Henry Rutgers, in the 18th century, leased out a piece of his land to a contractor, specifying exactly the size of the house the contractor could build. Too small a house might attract poorer tenants, too large might attract boarders, in either case altering the character of the neighborhood for the worse, degrading the value of his land.

In old New York, the gentry leased land to a contractor who would build a structure and rent it out to a single-family tenant. The building owner then extracted the rent on the residential tenant and in turn paid rent on the land to the landowner. Rutgers' specifications recognize that the value of land depends not just on the rent of whatever structure is built on it, but on the value of the land itself. For Ricardo, the value of the land depended on the demand for the best soil for cultivation. In a city, and for Rutgers, it's the demand for the best neighborhood, the cultivation of preferred neighbors.

So far Smith's analysis works well. The value of the land can be discussed independently from the rent of whatever is built on it. What I question is whether the value of the land can differ from the value of the buildings on it or their revenue.

The drawing at the top shows the Five Points neighborhood, lower Manhattan's notorious slum of the mid-19th century. The artist gives the impression of the topsy-turvy discord of the place, a kind of bizarro-New York. Wooden houses are sinking into the ground at different rates, street fights abound, a white gentleman is kicking a woman, presumably a prostitute, into the street while the only dignified character is the black gentleman in a top hat. Prominent among the incongruities is a tenement building, standing like a Trump Tower amidst a tattered Detroit street.

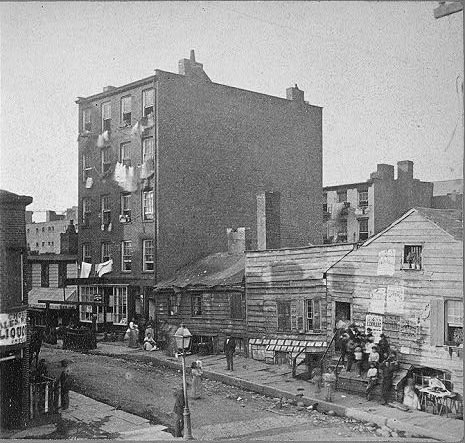

Here's a photo of the same street taken probably a few years later. You can see that the shack next to the tenement has sunk even deeper. In the drawing it's a two story structure, but the photo shows the ground floor window below the street level.

Charles Dickens had visited this very corner only seven years prior. He complains about the knee-high garbage in the gutter, and that's actually how this photo can be dated. The streets of Five Points were so filthy the city decided to "scrape" them clean in 1855. The story goes an Irish immigrant commented on seeing the newly washed streets of her neighborhood, "I had no idea there was cobblestones down there."

The cleaning of the foulest quarter of New York must have been quite the news. Five Points was not just the city's troubling social problem -- no one had ever seen such poverty, density or desperation in the city before, not to mention the concentration of Catholicism -- the place had also become a curiosity, a circus-like attraction. This photo was the instagram of its day -- The streets of Five Points have been cleaned?!? Definitely got to check that out and record it! -- and here it is, Five Points recorded ironically at its only clean moment, no doubt misleading many viewers today to think "It wasn't as bad as the literary accounts of it." Among the misled may be the viewers of Scorcese's Gangs of New York which reproduces dusty but barren streets, very much like the one in the photo. Here's what the streets of Five Points normally looked like:

Easier to see with this photo of a nearby East Side street lined with ca.1865 tenements, taken prior to 1894 when Colonel Waring finally got the streets of New York clean:

Not pretty. Dickens' complaint was no literary exaggeration. (Btw, if you look at photos of NYC streets in the late 1890's, you'll typically see cute little piles of horse shit here and there. They don't indicate that the streets weren't clean effectively. They're actually the mark of Waring's success. Priorly, you couldn't tell the horse shit from the heaps of excrement of all types, as above.)

Now take a close look at the tenement in the Five Points photo and drawing, in particular, what's behind the tenement in its lot. There's a back tenement -- a smaller tenement behind the main building. That little building tells all. I'll say a lot more about the reason for and the structure of the back tenement, but for now, let's just consider the mere fact that it's there.

In his contract, Rutgers also specified that there be no back house in his lot. A back house was guarenteed to bring a bad element. Who would rent in a back lot? Who would live in a front building with no back yard?

The mere existece of that back house says unambguoulsy that the landowner has lost faith in the neighborhood as a place where he would ever consider living in. He's abandoned its use to the exchange value of its building. That shift will send both the land and its building floating onto the current of exchange, of industrialization and immigration, and eventually to legislative reform.

And that's why it's so tall. At a time when the tallest townhouse was was three and a half stories, these tenements were the skyscrapers of its day. People of means spurned apartment buildings. Multiple dwellings -- they called them tenements, but they were just apartment buildings -- were for immigrant Catholics, not for dignified society. The decent lived in a house.

And it wasn't the tallest. But I will finish this story later. The real estate market, immigration, density, the lack of public transport, and most important, the owners' relationship with his land -- all influence the character of construction and of neighborhood. It's a story of an inverse relation between use value and exchange value that characterizes slum real estate, exactly the opposite of the non slum market where use and exchange and demand all rise together. In the slum, demand and exchange rise at the expense of use. The more demand, the higher the price, the worse the conditions and the greater the density. It explains the uniformity of the slum and its diversity over time. More soon.

In her Manhattan for Rent (Cornell 1989), Elizabeth Blackmar recounts how Henry Rutgers, in the 18th century, leased out a piece of his land to a contractor, specifying exactly the size of the house the contractor could build. Too small a house might attract poorer tenants, too large might attract boarders, in either case altering the character of the neighborhood for the worse, degrading the value of his land.

In old New York, the gentry leased land to a contractor who would build a structure and rent it out to a single-family tenant. The building owner then extracted the rent on the residential tenant and in turn paid rent on the land to the landowner. Rutgers' specifications recognize that the value of land depends not just on the rent of whatever structure is built on it, but on the value of the land itself. For Ricardo, the value of the land depended on the demand for the best soil for cultivation. In a city, and for Rutgers, it's the demand for the best neighborhood, the cultivation of preferred neighbors.

So far Smith's analysis works well. The value of the land can be discussed independently from the rent of whatever is built on it. What I question is whether the value of the land can differ from the value of the buildings on it or their revenue.

The drawing at the top shows the Five Points neighborhood, lower Manhattan's notorious slum of the mid-19th century. The artist gives the impression of the topsy-turvy discord of the place, a kind of bizarro-New York. Wooden houses are sinking into the ground at different rates, street fights abound, a white gentleman is kicking a woman, presumably a prostitute, into the street while the only dignified character is the black gentleman in a top hat. Prominent among the incongruities is a tenement building, standing like a Trump Tower amidst a tattered Detroit street.

Here's a photo of the same street taken probably a few years later. You can see that the shack next to the tenement has sunk even deeper. In the drawing it's a two story structure, but the photo shows the ground floor window below the street level.

Charles Dickens had visited this very corner only seven years prior. He complains about the knee-high garbage in the gutter, and that's actually how this photo can be dated. The streets of Five Points were so filthy the city decided to "scrape" them clean in 1855. The story goes an Irish immigrant commented on seeing the newly washed streets of her neighborhood, "I had no idea there was cobblestones down there."

The cleaning of the foulest quarter of New York must have been quite the news. Five Points was not just the city's troubling social problem -- no one had ever seen such poverty, density or desperation in the city before, not to mention the concentration of Catholicism -- the place had also become a curiosity, a circus-like attraction. This photo was the instagram of its day -- The streets of Five Points have been cleaned?!? Definitely got to check that out and record it! -- and here it is, Five Points recorded ironically at its only clean moment, no doubt misleading many viewers today to think "It wasn't as bad as the literary accounts of it." Among the misled may be the viewers of Scorcese's Gangs of New York which reproduces dusty but barren streets, very much like the one in the photo. Here's what the streets of Five Points normally looked like:

Easier to see with this photo of a nearby East Side street lined with ca.1865 tenements, taken prior to 1894 when Colonel Waring finally got the streets of New York clean:

Not pretty. Dickens' complaint was no literary exaggeration. (Btw, if you look at photos of NYC streets in the late 1890's, you'll typically see cute little piles of horse shit here and there. They don't indicate that the streets weren't clean effectively. They're actually the mark of Waring's success. Priorly, you couldn't tell the horse shit from the heaps of excrement of all types, as above.)

Now take a close look at the tenement in the Five Points photo and drawing, in particular, what's behind the tenement in its lot. There's a back tenement -- a smaller tenement behind the main building. That little building tells all. I'll say a lot more about the reason for and the structure of the back tenement, but for now, let's just consider the mere fact that it's there.

In his contract, Rutgers also specified that there be no back house in his lot. A back house was guarenteed to bring a bad element. Who would rent in a back lot? Who would live in a front building with no back yard?

The mere existece of that back house says unambguoulsy that the landowner has lost faith in the neighborhood as a place where he would ever consider living in. He's abandoned its use to the exchange value of its building. That shift will send both the land and its building floating onto the current of exchange, of industrialization and immigration, and eventually to legislative reform.

And that's why it's so tall. At a time when the tallest townhouse was was three and a half stories, these tenements were the skyscrapers of its day. People of means spurned apartment buildings. Multiple dwellings -- they called them tenements, but they were just apartment buildings -- were for immigrant Catholics, not for dignified society. The decent lived in a house.

And it wasn't the tallest. But I will finish this story later. The real estate market, immigration, density, the lack of public transport, and most important, the owners' relationship with his land -- all influence the character of construction and of neighborhood. It's a story of an inverse relation between use value and exchange value that characterizes slum real estate, exactly the opposite of the non slum market where use and exchange and demand all rise together. In the slum, demand and exchange rise at the expense of use. The more demand, the higher the price, the worse the conditions and the greater the density. It explains the uniformity of the slum and its diversity over time. More soon.

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

CB3

Went to CB3 last night. The liquor licensing committee seems to have improved its method of operations. The agenda indicated the time each item would be presented.

I didn't stay around to observe the action. The Distrcit Manager, as always, insulted me in her usual manner by telling me to get out of the way while I am actually not in her way as she walks right passed me with plenty of space to spare. She does this to me every time I attend a meeting, even though I never block an entry. Stupidly, I fell into the trap of responding to her incivility with my own, which, of course, doesn't do any good but just makes everything worse. I left feeling angry at her, angry at myself for being unpleasant to someone in her own workplace on her work time, and full of the frustration of having to want to justify myself yet still not being able to understand why she can't be civil and why I don't know how to let it roll off my back.

Of all the places I find myself, the Community Board 3 is without doubt the most unpleasant. The things that people have done there to me, the things that I have done there -- it's just a hellhole that somehow brings out the worst of human nature. At CUNY, where I'm teaching, the department is welcoming, considerate and fun, the students, despite all the pressures on them, are with few exceptions wonderful to be around, all the employees, from security to custodial staff, all charming to a fault, even the administration is at least pleasant and cooperative. Everyone seems to make an effort to please. Why is the community board so unpleasant?

Going to Community Board 3 reminds me of encountering the body builders who worked out on the chin-up bar in the park twenty years ago. They couldn't talk to you without telling you what to do, how to do it, that you're doing it wrong because you're not doing it their way, even though they weren't paying any attention at all to what you were doing, and what they were doing was limited at best. That's the community board in a nutshell.

I didn't stay around to observe the action. The Distrcit Manager, as always, insulted me in her usual manner by telling me to get out of the way while I am actually not in her way as she walks right passed me with plenty of space to spare. She does this to me every time I attend a meeting, even though I never block an entry. Stupidly, I fell into the trap of responding to her incivility with my own, which, of course, doesn't do any good but just makes everything worse. I left feeling angry at her, angry at myself for being unpleasant to someone in her own workplace on her work time, and full of the frustration of having to want to justify myself yet still not being able to understand why she can't be civil and why I don't know how to let it roll off my back.

Of all the places I find myself, the Community Board 3 is without doubt the most unpleasant. The things that people have done there to me, the things that I have done there -- it's just a hellhole that somehow brings out the worst of human nature. At CUNY, where I'm teaching, the department is welcoming, considerate and fun, the students, despite all the pressures on them, are with few exceptions wonderful to be around, all the employees, from security to custodial staff, all charming to a fault, even the administration is at least pleasant and cooperative. Everyone seems to make an effort to please. Why is the community board so unpleasant?

Going to Community Board 3 reminds me of encountering the body builders who worked out on the chin-up bar in the park twenty years ago. They couldn't talk to you without telling you what to do, how to do it, that you're doing it wrong because you're not doing it their way, even though they weren't paying any attention at all to what you were doing, and what they were doing was limited at best. That's the community board in a nutshell.

Sunday, June 15, 2014

Saturday, January 18, 2014

The Big Shrill

I moved to Loisaida in 1978 because it was hidden from mainstream New York, abandoned by ownership, undiscovered by commerce. The storefronts that weren't lived in were empty, aside from a very few store survivors from the past. No one thought the lack of commerce was a problem. To the contrary, anarchists railed against the threat of gentrification, although their target was the police, go figure.

Today the community board worries about filling every storefront as if the welfare of landlords, who most benefit from commercial rents, were a matter of public community concern. And what moves community activists today is SantaCon, as if a single day of silliness merited anyone's trouble. SantaCon is good for a laugh, but at least the Santas don't throw eggs as the kids used to decades ago on Halloween. This neighborhood sounds like the Upper East Side complaining about an ethnic parade down 5th Avenue.

The sign that the LES is truly gone and buried is this character of its activism. When did the defense of anarchy and difference turn into defending middle-class vaules of quiet, normality and the absence of disruption?

Today the community board worries about filling every storefront as if the welfare of landlords, who most benefit from commercial rents, were a matter of public community concern. And what moves community activists today is SantaCon, as if a single day of silliness merited anyone's trouble. SantaCon is good for a laugh, but at least the Santas don't throw eggs as the kids used to decades ago on Halloween. This neighborhood sounds like the Upper East Side complaining about an ethnic parade down 5th Avenue.

The sign that the LES is truly gone and buried is this character of its activism. When did the defense of anarchy and difference turn into defending middle-class vaules of quiet, normality and the absence of disruption?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)