Some years ago (14? 15?) I was walking back home through TSP from a civil disobedience arrest -- earlier in the day I'd intervened with a cop giving a bike ticket to an elderly Latino who'd innocently biked through the intersection of 11th and B on a Saturday morning with no traffic anywhere in sight (except the cop car). The cop was already incensed, since he'd been barking orders over his car megaphone trying to get the old man to get off his bike, this cop too dim (nothing against the force -- some are smart, others not) too dim to grasp that the old man obviously didn't know a word of English and had no clue he'd done anything wrong and the cop too lazy to get out of his car and use gestures to explain himself. I knew the old man -- he bagged groceries for the local supermarket. A $100 fine would be more than he could afford, probably ten times more than the price of his funky third-hand bike. After I tried, nicely, to persuade the cop to let the old guy go, the cop brushed me off insultingly when he'd done with the ticket. I yelled back at him, "Get out of my community," for which he arrested me. I'd already been arrested for civil disobedience a couple times before (was this civil disobedience or just self-expression?) so I didn't think much of it, but my roommate, a gentle soul not from New York, who saw it from down the block, was terrified. If you break the law and are arrested for it, at least you know what the charge will be and something of what to expect from the police. But if you're arrested for nothing illegal but for angering the arresting officer -- well my roommate was convinced he'd never see me alive again.)

So I was coming back from this arrest -- as it turned out, the two hours I spent in the holding cell was passed with talking to the cop, intermittently explaining why ticketing old immigrants just to raise city revenue or personal quotas is really shameful. By the time the two hours were done, he was embrrassed enough that he wrote up the charges intentionally so that the judge would throw them out instantly -- disorderly conduct for talking back to an officer. Several weeks later in court, the senescent nonagenarian judge did dismiss it along with a doddering admonition to me that I should be more respectful, young man.

Well, coming back home I ran into Hippie. "Hippie" is not actually his name, of course. From Puerto Rico, here he was called "Hippie" for his long, flowing, reddish pony tail. I asked Hippie what he was doing back in the neighborhood. Since he'd been released from prison -- some stupid drug charge I suppose, I say stupid because Hippie was one of the most honest, decent, charming, pleasant men I've known -- he'd been diagnosed with Hep C, so the Dept of Social Services had arranged a free apartment for him in Brooklyn, yet here he was homeless and couch-surfing in Loisaida. "Hippie, you have an apartment, you're seriously sick and then some, why are you hanging here homeless?"

"I always come back to this neighborhood. I come back here for one reason and I can tell you why. Because it's mixed. I don't want to live in a ghetto. I always liked that this place is mixed. It was mixed back then. It still is."

That was about 14, 15 years ago. I don't see Hippie anymore. So many of the best are gone.

I grew up in a white 'ghetto.' Sometimes I ride my bike past it, but I never stop. It wasn't much interesting back then, and it's just as uninteresting today. For a while I lived up in Inwood -- huge, bright apartment, immense rooms; the hallway between the livingroom and the den so wide I had a piano in it -- a view of the Cloisters from my bedroom window, and cheap rent too. I was never happy there.

It's only been in Loisaida that I've found that urban mix, even when it was most abandoned -- because it was abandoned, abandoned by ownership, abandoned by commerce, abandonned by law and all authority. Landlord? Invisible. Work? No one worked except the dealers. The only people who cared about what you did were the people you lived with on the block. It was scarier than it was dangerous, but it was too scary for slummers. The place drew only outcasts, loners, misfits and marginals. And artists -- blacksmiths, poets, muralists, brilliant muralists, their work all gone.

Some places are more interesting than others, some more extreme, some more free; few are all those together. Never say NeverNeverLand never existed if you never lived there once.

David Graeber's recent book on debt ends with a defense of the chronic unemployed. He hints that maybe the economically unproductive are actually busy with useful services to their local communities.

Previously

the feeling for place -- the sacred and the profane;

sacrificing for progress

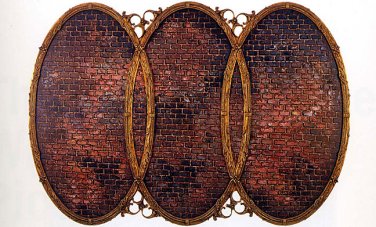

The work of Martin Wong, the only way to understand what we saw. Photography captures nothing -- nothing -- of a space so emotionally rich.

No comments:

Post a Comment